Reading Programs with Donald Knuth

I believe that the time is ripe for significantly better documentation of programs, and that we can best achieve this by considering programs to be works of literature

In 1984 Donald Knuth published a short paper describing a way of making software he called “Literate Programming”. Its a concept that gets lots of mention in Software Studies and even some within Software Engineering, and one that was very appealing to me when I first read about it as a CS / English Lit double major lo these many years ago. I’ve always thought about it as a style of writing. But of course, it should have a corresponding practice of reading. I haven’t read a ton of Knuth, but I’ve never seen anything on reading literate programs (I’d love a pointer if anybody knows of any!).

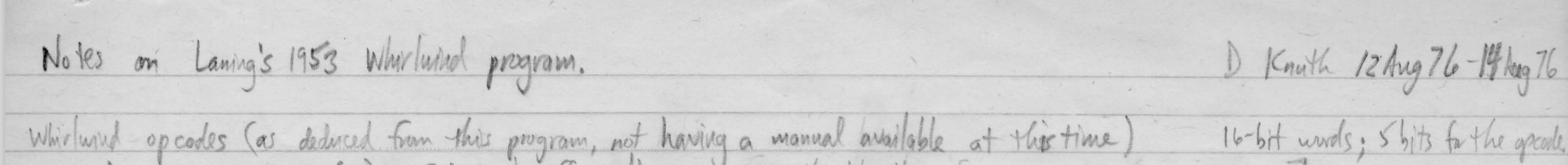

I recently found a cool example of Knuth’s own reading practice. It’s a set of handwritten notes on a “program for translation of mathematical equations for Whirlwind I”. It was a program which took in properly formatted strings that represented algebraic equations, and output computer code that could be run on Whirlwind I to solve them. The Computer History Museum has the text of the original program and four pages of handwritten notes from Knuth, as he deciphered the program over several days in August, 1976.

Knuth conducted this research for The Early Development of Programming Languages, which surveys a number of early systems that could claim to be programming languages. The paper was co-authored with Luis Trabb Pardo (who I cannot find any biographical information about) and implements the Trabb Pardo-Knuth (or TPK) algorithm in each of the systems they describe.

Note that the same algorithm will be expressed in each language, in order to provide a simple means of comparison. A serious attempt has been made to write each program in the style originally used by the author of the corresponding language; and if comments appear next to the program text, they attempt to match the terminology used at that time by the original authors.

The algorithm serves no purpose except to demonstrate how the different languages handle input/output, looping, and branching. Its a lovely piece of comparative technical history, using a method which gives us a hint of what each language was capable of expressing and the style its authors used.

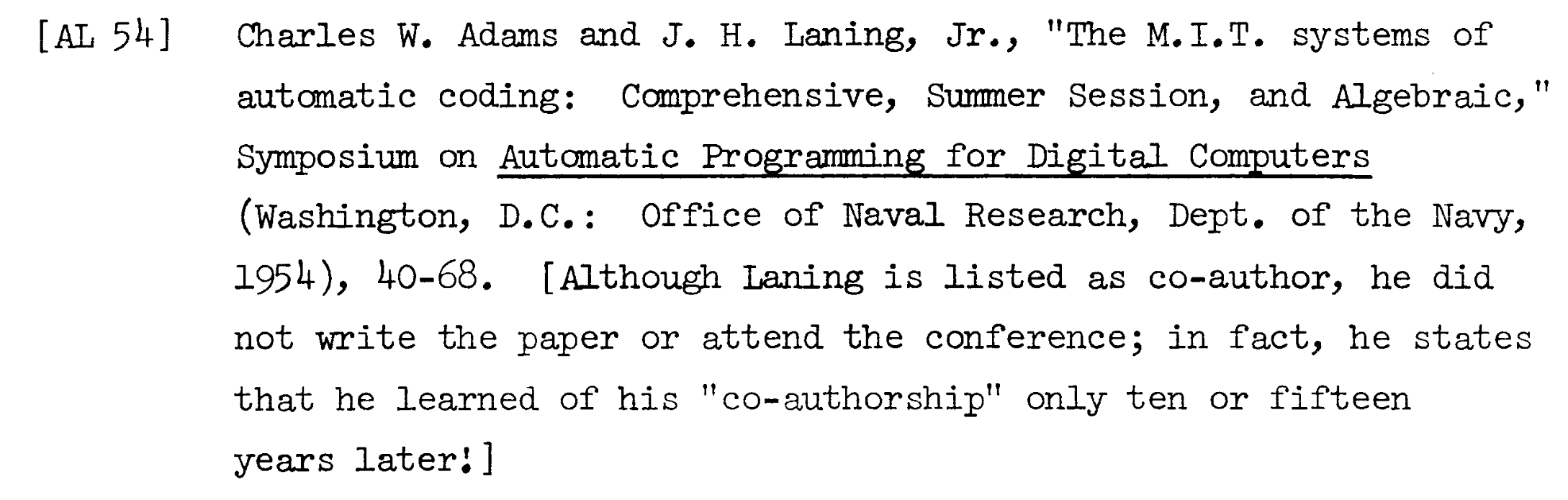

One of those systems was J. Halcombe Laning, Jr. and Niel Zierler’s 1954 translation program. The manual for the program was published by MIT’s instrumentation laboratory as a technical report (E-364), and described in a paper for the 1954 “Symposium on Automatic Programming for Digital Computers”. This meeting, organized by Grace Hopper for the Office of Naval Research, was an important early step in forming a community around programming languages. Amusingly, Trabb Pardo and Knuth note that while the paper listed Laning, Jr. as a coauthor, he wasn’t even aware of its existence at the time!

Knuth and Trabb Pardo argue that while this particular system didn’t spread beyond MIT, it was very influential in this small American automatic programming community. Additionally, they point out that this was perhaps the first attempt at abstracting notation beyond the physical computer which would execute the instructions: “The programmer no longer needed to know much about the computer at all, and the user’s manual was (for the first time) addressed to a complete novice.” (56) As Laning, Jr. and Zierler put it in the introduction to the program manual “the effect of our program is to create a computer within a computer”.

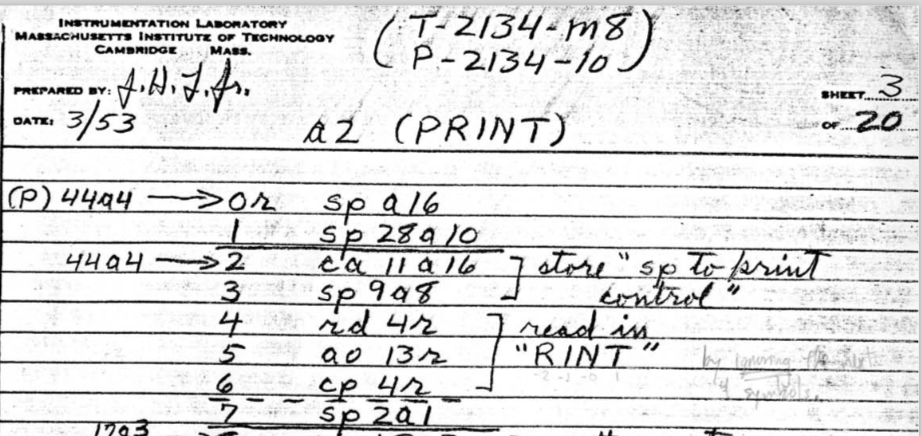

The scan available online features the program written out in Laning’s handwriting with Knuth’s notes in the margins.

For example, in instructions 4-6 of the PRINT subroutine, we can see Laning’s comment “read in RINT” and Knuth’s realization that the program does so “by ignoring the next 4 symbols.”

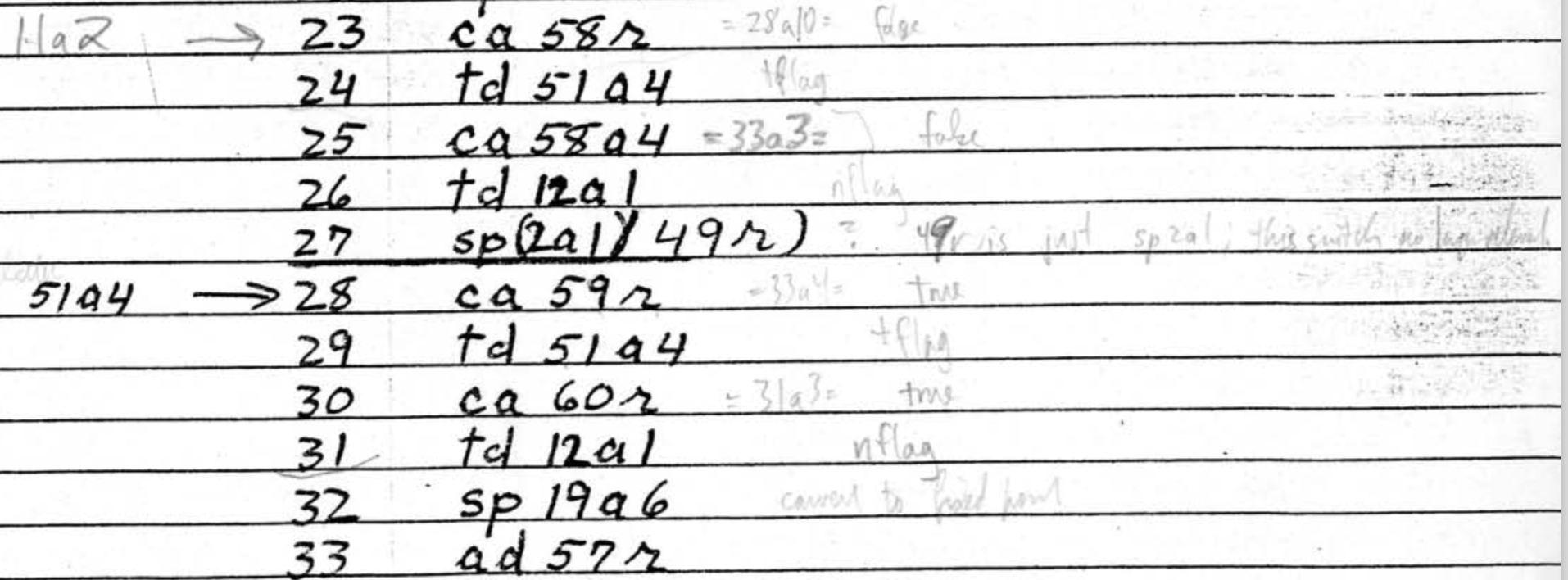

The original program itself has fairly extensive commenting. Subroutines are labeled, the location of the symbols is noted, and certain sections that do unexpected things are highlighted. Knuth adds his own understanding below some of these comments (as with the RINT routine). He also marks up more low level details of what particular instructions are doing, tracing values as they go through different parts of the program:

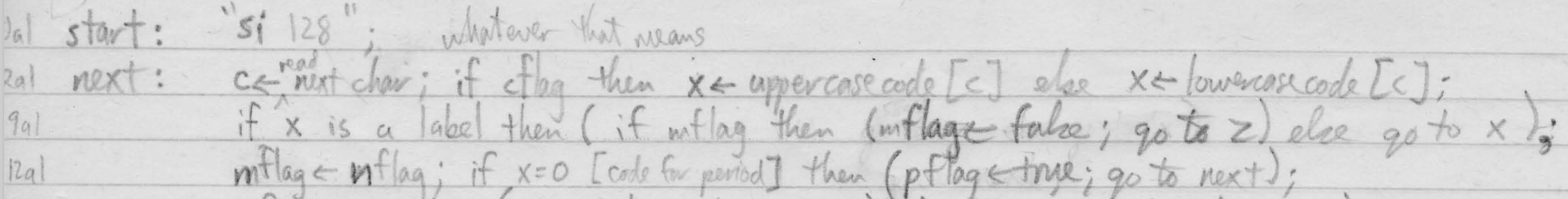

In a separate file, the CHM has a scan of 4 pages of notes that Knuth produced from his readings. As shown at the top of this post, he reproduced a listing of Whirlwind opcodes based on the program listing (a pretty remarkable bit of technical sleuthing!) Additionally, he rewrites the program in an Algol-like pseudo code:

(I love the ‘Whatever that means’! Right at the beginning of the program)

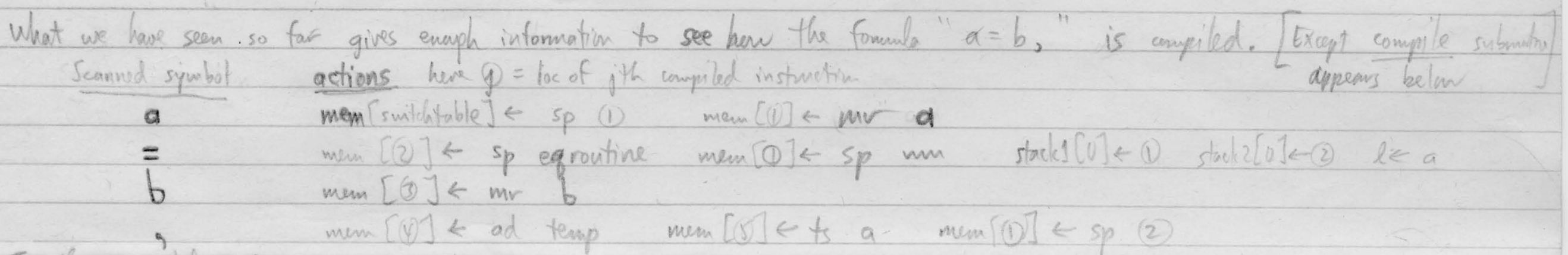

After rewriting the program, he works through a small example, showing how “a=b” is compiled by the system:

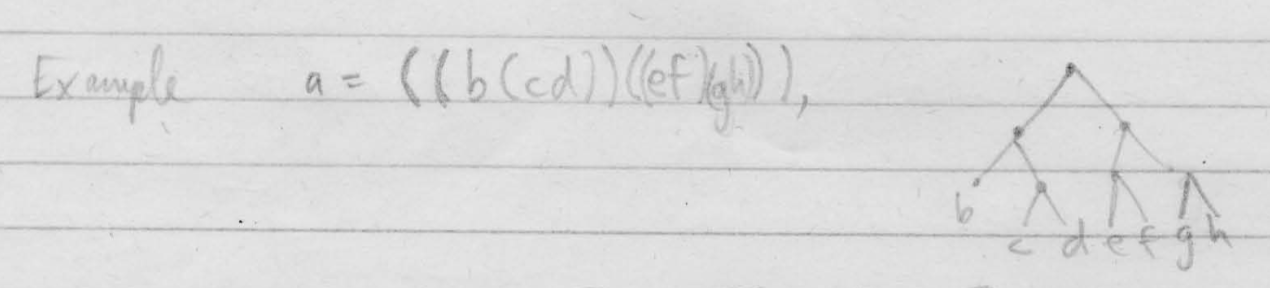

After walking through the compiled output, he works through a more complex equation: “a=3.1b - c/d2”. And finally, he works out an example that shows how the system parses balanced parenthesis:

Now, obviously this program is far from “literate” (its an assembly program written 30 years before Knuth coined the term) but I think we can still take something away from Knuth’s “reading” of it. First is that Knuth is not just reading the program text. The comments inform his understanding and he references personal correspondence with Laning Jr. Second, Knuth’s reading involves a lot of writing! He reproduces the program at a higher level of abstraction, writing it “in his own words”. Finally, reading required running the program. Now, Knuth did not have access to Whirlwind, so the program was not executed by a computing machine. But Knuth ran through specific examples himself, documenting how data flowed through the system.

I really enjoyed following in Knuth’s footsteps and trying to form my own (limited) understanding of the program. I don’t think Knuth had access to the program user manual, but its available online. I only skimmed through it for this post, but perhaps I’ll dive deeper into it next.