Gravitation

Jason Rohrer describes his Gravitation as “a video game about mania, melancholia, and the creative process”. In Newsgames it is provided as an example of a “human interest” game, commenting on games’ “ability to reconstruct personal emotional experiences rather than just describing them” (Bogost et al, 2010). The game explores Rohrer’s cycles of creative mania, and places the player in the position of balancing “abstract, difficult work, and its interplay with the inspiration that comes from family interaction” (ibid.).

The game opens with your character in a small box of visibility tinged with gray, the rest of the screen obscured by blackness. To the right of the screen is a furnace, and moving to the left reveals a small child avatar who begins throwing a red ball to you. If you bat the ball back, a heart appears over the child’s head, but if you don’t and the ball hits the ground, tears sprout from the child. As you play ball, the visible box grows larger, and the area within becomes more colorful and brightly lit. This is a simple, powerful ludic metaphor for depression, its antidote being human interaction with loved ones.

At a certain point, when your “mood” raises high enough more of the world is revealed, your head appears to catch fire and you can jump incredible distances. Jumping above your starting level reveals stars, which fall downwards when touched. Your “mania” only lasts a short time, after which your view closes up and the colors darken again. Unable to jump higher, you navigate your way down to the original level, where the stars have become blocks of ice with point values. The points start at 9 and count slowly downwards. Pushing the blocks of ice into the furnace on the right of the screen adds their current point value to your total. The child continues to throw the ball when you return, though the piles of ice can cut you off from him until they are cleared off. Initially, straining against your arrow keys can feel difficult as the ice moves slowly towards the fire. Playing ball with the child increases your mood, and if you re-enter mania ice piles can be cleared more quickly.

There are several additional aspects that make Gravitation an interesting work of literature. Firstly, while playing with the child can increase your mood, it does not increase your point total. It is possible to play through the entire game just batting the ball around, but your score will remain 000. You also do not receive points for harvesting the stars, only for pushing the blocks of ice into the furnace. While you have spurts of depression when you are exploring the space above the ground level, they can be waited out and your mania will return. You can continue to explore the heights of pure creativity above for the entire game, but without the difficult work of pushing those ideas into the furnace, your score remains 000.

This constant returning to the home level makes Gravitation feel like a balancing act, enforcing the work-life balance theme that is at its core. Gravitation’s most moving portion comes towards the end of the game. At a certain point, while you are collecting stars above, the child leaves. You return home to find the ball sitting alone on the ground. Mechanically, the game continues unchanged, but the emotional tenor shifts drastically. Collecting your stars begins to feel empty.

One of the key components of the game’s atmosphere is the music, which keeps pace with the shifting mood. In the beginning of the game, the music is slow and mournful. As your mania increases, the initial music becomes overlaid with other tracks, which fade out again as your mood darkens. The volume and tempo increases and the music becomes discordant as your mood intensifies.

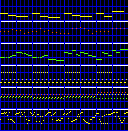

Rather than a typical audio type like .ogg or .mp3, the game’s music is encoded in a .tga file, an extension most typically used for image files. In fact, if you open the file with an image viewer, it reveals waves that appear to represent six different musical tracks.

The thicker white horizontal lines delimit the different tracks. The first track has long yellow lines that correspond to the slow, low brass sounding initial track. The second track has small red dots, that sound like a xylophone. The third green track is the initial melody. The next three tracks are activated during mania, and its build up. The two tracks with many small dots spaced at regular close intervals to each other appear to be the game’s drum tracks. The last track has yellow dots which only play during the height of mania, and provide a rapid, high pitched counterpoint to the initial melody.

Investigating the musicPlayer.cpp file (lines 17-20) reveals that the music changes based on the game state:

// smoothly fade in particular tracks based on player emotion

// low emotion plays only first track... high emotion plays all tracks

extern double playerEmotion;

Rohrer’s comment (delimited by the double slash marks) precedes the floating point variable “playerEmotion”, which represents the avatar’s emotional state. It operates on a scale with 0 being total melancholia and 1 being total mania. It is used later (lines 233-236) as a multiplier for fading tracks in and out.

// factor in player emotion

// level from 0..(numTimbres-1)

double trackFadeInLevel = playerEmotion * (numTimbres-1);

Music is not the only place the playerEmotion variable comes into play. It is initially set in game.cpp (lines 536-538) with comments to explain its usage:

// 1 = manic

// 0 = depressed

double playerEmotion = 0.4;

Several lines later Rohrer defines another variable:

double defaultDeltaPlayerEmotion = -0.0010;

double deltaPlayerEmotion = defaultDeltaPlayerEmotion;

The second variable, deltaPlayerEmotion, is the rate at which player emotion changes each frame of the game, and is initialized to -0.0010, meaning that you begin the game on a downswing. In the next few lines Rohrer defines several upswing variables that provide a “natural depression recovery” (line 548). These variables provide a snapshot of the fairly simple system Rohrer uses to model human manic depressive cycles. It affects everything, from the music to the size and color of the visible world.

In this code Rohrer is treating the “playerEmotion” to be state of the game player’s avatar, not the player themselves, which would be much more difficult to assess. However, the discordant music will affect the human player’s mood. By tying the visual and auditory representation of the world to the avatar’s emotional state, Rohrer can change the human player’s mood. Even the mechanical changes, such as increased strength and jumping ability serve to make the player feel powerful during mania and weak during depression.

Playing ball with Mez increases the playerEmotion variable, by 0.15:

if( mezCaughtBall ) {

playerEmotionSmoothTransitionTarget = playerEmotion + 0.15;

playerEmotionSmoothTransitionTarget gives the point that playerEmotion is aiming for, but Rohrer slows the transition for a less abrupt jump upwards. In a separate World.cpp file I found the portion of the code that explains the way touching stars, or prizes as Rohrer calls them, changes your emotional state. From within a function named touchPrize (line 1374-1378):

// renew mania

playerEmotionSmoothTransitionTarget = 1.0;

// accellerated descent toward depression

deltaPlayerEmotion *= 2;

The first non-comment line resets your current emotional target back to full mania, while the second line of code doubles your rate of descent. It results in the sometimes wild swings of emotion that can be experienced while searching for stars. This is one of the most fascinating portions of the code, as it reveals something new that I was unaware of from playing the game alone. It was apparent that touching prizes had some effect on your emotion, but I was unaware of the doubled descent into depression. From a rhetorical perspective, this rule has some fascinating implications. Collecting the prizes is actually a faster way to gain mania, but note that the accelerated descent is a multiplier not a fixed value. Collecting five prizes in a row would result in a tenfold increase in your downswing. This is in contrast to the slower mania building of playing ball which has no such emotionally turbulent side effects.

game.cpp also contains the code controlling the child’s disappearance (lines 1406-1414):

// last 3/8 of game

if( timeLeft <= 0.375 * totalTime ) {

// mez "sneaks" away if he's off screen near the end of the game

if( ! isMezOnScreen() ) {

hideMez();

}

}

Several things are happening in this code. The first line is a comment explaining that the second line determines how much time is left in the game as a ratio to the total time of the game. As the next comment explains, after that point, any time the child is off screen he will leave. The isMezOnScreen() function returns Mez’ location on screen. A null value, meaning Mez is offscreen, will be interpreted as false by the if statement. The exclamation point can be read as “not”, so the entire line checks if Mez is being displayed, and if not, moves to the body of the if statement, hiding Mez.

In some ways seeing it in code is anticlimactic. It clarifies some things about the game. The child is a boy named Mez, after Rohrer’s son. His disappearance is nearly inevitable, unless you spend the entire last 3/8 of the game with him. Furthermore, there is no chance of Mez remaining if you leave.

When explained in clear code, this portion of Gravitation can be read as an exploration of the parental impulse to “helicopter parent”. On the one hand, doing so prevents the child from moving on to a fruitful adulthood, but in Gravitation you cannot watch Mez grow up. A boolean true/false value gives you no middle ground.

There is much more to explore in the source code of this game. It is very clearly written, profusely commented, and from both a programmer’s and literary critic’s perspective it contains some clever tricks. I am particularly interested in locating where the score is calculated. While it seems to be a clear linear reduction of points after the ice blocks hit the ground, investigating the code would verify the algorithm.

The most interesting aspect of Gravitation’s platform is that it is open source, enabling this paper. The openness of the code allows people to swap in new music files, changing the tenor of the entire experience. It also enables anyone to modify the game the way they believe it should be. In a different version of the game it could be possible to score just as many points by remaining with Mez and playing ball. Such a game would be procedurally portraying different values, and would be a significantly altered game, without the balancing act that makes Gravitation such a challenge.